Strategic Charity: Mexico and the Spanish Refugees

Ann Elisabeth Laksfoss Hansen

ILASSA Conference, Austin, February 1999

|

Autobiography

I was born in Haugesund, Norway in 1970, where I

lived and went to school until 1987 when I spent a year in Granby, QC, Canada

as an exchange student. In 1990 I

entered the University of Oslo and while studying Spanish and History there I

also include one year as a Georgia Rotary Student in Americus, GA, where I

studied Japanese and Political Science In addition to this I did one semester

of Spanish History at the Autonoma de Madrid, all of which is included in the

BA from Oslo University (1994). After

graduating I returned to Madrid for a MA in International Relations from Instituto

Universitario Ortega y Gasset, and I studied did both a summer course in

French in Montpellier and in Portuguese in Braga, Portugal on a Luis Camoes

scholarship. In 1996 I went to Ohio

University where I studied American History on a Fulbright scholarship. After graduating from OU with a MA, I

transferred to University of Texas at Austin in fall of 1997. From UT I received a MA in Latin American

History spring 1999. For the past school-year I have

also taught Spanish at the University of Texas. Future plans include finding a fascinating job, but first I am

off to North Western Argentina, where I will accompany my beloved Nestor on

his geological expedition. Ann Elisabeth Laksfoss Hansen Geitafjellet

1B 5521 HaugesundNorway #

47 52728191 |

An eight-year old boy walked

wearily down the gangway from the ship Mexique. In his right hand he held a blue cardboard

suitcase, while his sister clung to his left hand. Emeterio and his three younger siblings arrived in Veracruz on 7

June 1937, in a group of 463 children, all traveling without their parents who

remained in Spain. Thousands of

Mexicans, touched to tears, watched the "güeritos"(little blond ones)

as they disembarked, and the sight prompted spontaneous offers of adoptive

homes, but President Lazaro Cárdenas declined these offers.

This scene is part of the

story of Spanish refugees arriving in Mexico in the late 1930s. The coming of these Spaniards can be

understood in the context of Mexican sympathy for the Spanish Republic, and it

certainly followed Cardenist ideas of international solidarity and cooperation. Mexican revolutionary rhetoric of the 1930s

outlined the methods by which Mexico would modernize. In this political project the government actively promoted the

image of an advanced, and humanistic Mexico.

By inviting Spanish refugees during and after the Spanish Civil War,

Mexico promoted its country internationally and encouraged internal cohesion.

The focus on Spanish

immigrants attempts to explore some of the premises of the Mexican immigration

practice in the late 1930s. Mexican

government officials offered economic and cultural reasons for preferring

"Latin" immigrants; but concepts of ethnicity, also played an

important role. The expression of

ideological affinities and exploitation of this immigration for propaganda

purposes illuminate the premises of this strategic charity.

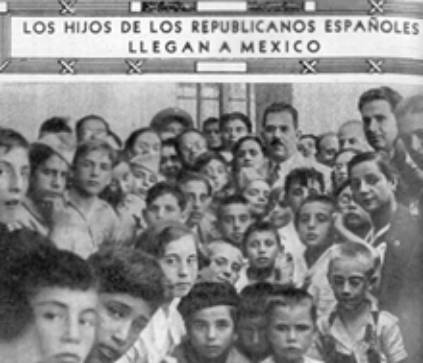

THE SPANISH CHILDREN

Scrutinizing newspaper

editorials and diplomatic papers from some of the highly publicized voyages of

Spanish refugees offers clues as to the attitudes toward immigration in the

late 1930s. In June 1937 a group of 463

so‑called "war orphans" sailed from France to Veracruz on the Mexique. While they were victims of war most of them

were not orphans. Their Republican

parents and even a few Francoists had chosen to send their children out of the

war zone.[1] These are only a fraction of the approximately

22,000 Spaniards who arrived in Mexico from 1937-1949. This shipload, in many ways extraordinary

since only children came, serves as an example to analyze what some Mexicans

thought about Spaniards in specific and immigration more generally.[2]

Motivations for sending the children were diverse. Basically parents wanted to evacuate their

children from a country in war. Mexican

social worker Vera Foulkes, who investigated the event in the early 1950s,

suggests that some parents sent their children so that they could participate

more actively in the fighting.[3] Emeterio Payá Valera, himself a

"Morelia‑child," points to discipline problems, insinuating

that some of the children had been troublemakers in Spain, a condition which in

certain cases worsened over time.[4] It is doubtful that the parents should have

perceived the separation as permanent when they decided to send the children

overseas. It seems more plausible that

they should think of it in terms of a temporary separation. However, in the end only some sixty children

ever returned to Spain. The Mexican

motives for receiving the children were equally diverse. There is little doubt that Mexican charity

played a role, but equally valid are

concerns involving the propaganda opportunities the group of children brought

with it. With little investment Mexico

received positive publicity and stood out as a model for humanitarian behavior.

Political turmoil followed the children wherever they

went. The Spanish Republican government

used the publicity surrounding the children to gather political support for its

cause.[5] Kuhn reported that once the Mexique

reached Havana, Franco sympathizers

claiming that the children constituted "live" propaganda, and

therefore prevented the children from going ashore.[6] Payá does not remember this episode, but he

recalls that when the ship approached Havana, Cubans in boats cheered them with

Republican flags and political slogans.[7] Whether the children had to stay aboard or

not, a committee of pro‑Republicans and Spanish diplomats provided a warm

welcome by visiting while the ship was docked in Havana, and the children left

Cuba on their voyage to Mexico, their "cheeks lumpy with candy."[8]

Mexico, moved by Republican plights, offered to evacuate children

threatened by war. The evacuation of

Spanish children started in 1937, after Franco's forces had bombed Guernica and

other cities for months. The Mexican

government supposedly at the initiative of Amalia Solorzano de Cárdenas, the

president's wife, offered to bring in five hundred Spanish children.[9] What touched Mexican sympathies the most

were pictures of dead and wounded children after the bombardment of Madrid.[10] These reports spurred the creation of help

committees across Mexico. The Committee

for Assistance to Spanish children in Merida and Yucatán, collected more than

two thousand children's outfits, and shipped them via France to reach Spain, on

the same Mexique, which then and transported 463 Spanish children to

Veracruz.[11] The Mexican press reported from the horrors

of the Civil War every day and these horrors moved Mexicans to wanting assist

Spaniards.

Both strategic

and philanthropic motives guided the Mexican government’s decision to receive

the children. Historian John W. Sherman

suggests that Cárdenas, by inviting the children, managed to disarm his

conservative opposition by appearing as the quintessential protector of

children, countering attacks accusing him of being anti‑family.[12] The news reports of Fascist atrocities moved

Mexicans. Roberto Reyes, the director

of the España-México, makes special reference to an exposition about the

Fascist barbarities, organized by Frente Popular Español in Mexico. Mexico was not the only country to receive

groups of children; Russia welcomed 2,895[13]

and England received 4,000 youths.[14] Although numbers are unavailable, France

probably received many more, due to geographical proximity, and the fact that

we know roughly 500,000 Spaniards sought refuge in France during the civil war.[15] The uniqueness of the Mexican case consisted

in the children forming part of an experiment of cross-cultural understanding

and learning, in a country which earlier had been a colony under Spain, and

which had a considerable colony of Spaniards living in it. Also most of the in all 34,000 children at

some point evacuated from Spain returned to Spain.

Over four hundred Spanish

children lived and learned with one hundred Mexican children in Morelia. The president chose to establish the España-México

school in his own home state Michoacán.

The school constituted a perfect opportunity for an experimental

project. In Morelia the administration

could implement humanism and international solidarity in a controlled

environment. Director Reyes recalled

the children "like an invasion of whites among the brown (tostados)

children of military officers."[16] Cárdenas thought this living experience

would "establish between them a current of sympathy and solidarity."[17] It is possible that his last objective

materialized although it is difficult to measure whether with regard to degree

of integration, sense of belonging or identity. The school's organization in Morelia, is an example of how the

government thought about the children in terms of a social project between two

nations: Spain and Mexico. Although

several families offered to adopt the children, the government declined this

offer, insisting on the importance of keeping the children together as a group.[18] The Cardenist administration's ambitious

project of transforming Mexicans through education includes the invitation of

the children. In addition, Spanish

Republicans and the pro‑Cárdenas Mexicans forged deeper ties and Mexico

received favorable international publicity.[19]

THE STATE AND THE CHILDREN:

FLASHLIGHT PUBLICITY

By evacuating

the children Mexico projected itself internationally as a modern, resourceful

country capable of undertaking responsibilities suitable to modern

nations. The president explained that

the coming of the children was the result of altruistic, Mexican women ‑‑

among others his wife Amalia, here presented as Mother Mexico, who had insisted that something be

done. But the children called the

president "tata" not only because he was as fatherly to them, but out

of respect. Cárdenas became their

symbolic father.[20] The coming of the children marked an event

for the Cárdenas propaganda apparatus; as Mexique entered Veracruz

journalists filled the port. The Communication Department even engaged a

photographer to film the event. In

addition, strategically placed microphones transmitted speeches and grateful

testimonies from the children to Mexico, and in particular to Cárdenas on

national radio.[21] The conservative newspaper Excélsior

sent special envoys to cover the arrival in Veracruz, where crowds of waving

and cheering Mexicans welcomed the children.[22] Government supporters sympathized with the

cause of the Spanish Republic, and the arrival produced numerous curious

spectators at the port. 30,000 Mexicans

waited at the train station in Mexico City.

Both Mexicans and Spaniards had left their houses and spontaneous cries

of ¡Viva México! and ¡Viva España! filled the air.[23]

The administration orchestrated the event

beautifully. (see photo of Cárdenas with the children) The Communication

Department, a part of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, transferred the

responsibility of the children to the Ministry of Education, thus suggesting

the event's propagandistic utility.

Mexico took advantage of the occasion, and DAPP produced a short‑film

called "The Spanish Children in Mexico." The film belonged to a series of "shorties" sent and

shown throughout Latin America in this the golden age of Mexican cinema,

covering all the wonders of modern Mexico, and depicting the successes of urban

planning, sewage systems, and highways.

In short, Mexican propaganda proclaimed the country to be the advanced

nation the rest of Latin American should follow. "The Spanish Children in Mexico" played for two months

in Santiago de Chile, and for a wide audience ‑‑ including

President Alcibiades Arosemena ‑‑ in Panama. Mexico even sent the film to Barcelona where

as many as 50,000 Republicans, including Luis Companys, watched it.[24]

Before the curtains went down of the media show in

Veracruz, Hidalgo transferred

the responsibility of the

group to under‑secretary of Education Luis Chavez Orozco, with the final

words, more directed to the Catholic opposition than to exhausted children

between the age of three and fourteen:

And now I address myself to

you cubs of the old Spanish lion. From today on you will remain under the

protective wings of the Aztec eagle . . .![25]

Hidalgo's words to meant to

calm the critical Catholics who claimed that the whole expedition had resulted

from Bolshevik perversity, which produced traitorous parents without family

values.

Both pro‑children and skeptics alike considered

the children more as ambassadors for the Spanish Republic than as refugee

children. The opposition accused the

government of preferring international prestige above suffering Mexican

children, while the pro‑Republicans celebrated the event as a victory for

Mexican humanism and international solidarity.

J.R. Hernandez, in an editorial for El Universal called the

evacuation "positive human solidarity" and went against critiques

calling it superficial and false.[26] Critical voices spoke up about Mexico

receiving the children in Excélsior editorials during the spring of

1937. Before the group of children

arrived a parliamentary representative even suggested that the "Iberian

colony" in Mexico should be taxed extra to finance the children's

maintenance.[27] Another editorial opposed the idea of extra

taxes, "It would not be very decorous" for Mexico to rely on

foreigners to finance this sort of project;[28]

accepting and providing for the children, it continued, was typical of

Cárdenas's charitable and political support to the Republic.[29] The criticism did not end after the children

had arrived. Querido Moheno Jr.,

criticized the government for indoctrinating the children, while welcoming the

income of "much needed" Spanish blood.[30] An ambitious Moheno hoped that Mexico, by

caring for Spanish children in a responsible way, could bridge ideological

differences and "conquer in the spirit of these children the gratitude of

Spain, all of Spain and the recognition of the world, and of everybody."[31]

Although the

political establishment favored it, not all Mexicans warmly embraced this

immigration, and many fervently opposed the coming of the Spanish

Republicans. The American Consul

General in Mexico, James Stewart, noted that the press clearly reflected the

reluctance of some Mexicans' to welcome Spanish immigrants.[32] The Mexican upper class, the Catholic

Church, Sinarquists, and right‑wing politicians all expressed their

concerns, as did elements from the conservative "old Spanish

colony." According to Stewart the

opposition feared that radical leaders, such as Lombardo Toledano of the Confederation

of Mexican Workers (CTM), would promote the immigration with the objective of

transforming Mexico into a Bolshevik state.[33] Neither the opposition nor the

administration differentiated between the arrivals; for Mexicans both the

children and the ex‑combatants, who came after the Spanish Civil War represented

the Republican cause.[34]

Mexicans did not distinguish

between the refugee children of 1937 and the political refugees who came

later. It is problematical to call the

children who came in 1937 Republicans because of their age, but at least they symbolized

their parents' Republican beliefs to Mexicans.

In 1937 the children aboard the Mexique could not enter Havana,

just as the Republicans onboard the Sinaia in 1939 were unable to go

ashore in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

While Mexico received the Spanish immigrants, and the majority of these certainly became loyal supporters of Cardenismo, they failed to integrate in the way Cárdenas had hoped. Cárdenas foresaw Spaniards becoming the warriors of agricultural development at the Mexican frontier, similar to European immigrants who induced development in the United States, but the colonization projects in northern Mexico fell apart due to harsh climate, inefficient administration, and internal disagreement among Republicans.

CONCLUSION

The Mexican government

enthusiastically welcomed the Spaniards because it perceived that the related

language, religion, ideology and ethnicity would facilitate integration. Even though revolutionary rhetoric sought to

eliminate race, and replace it with the more encompassing concept of culture,

racial preferences still prevailed in the 1930s. The ideal immigrant remained Spanish.

The Cardenist government, in true populist fashion of the period, used the media to project the image of a modern, advanced nation, fully qualified to receive immigrants. For once Mexico could decide whether to reject or to welcome large groups of Europeans. The newly established propaganda agency (DAPP) used radio, newspapers, and films, and sent it all abroad as publicity, advertising the triumphant heritage of the Mexican Revolution by showcasing humanism and solidarity. The Spanish children who came in 1937 were perfect for the media machine, skinny, fearful children with big eyes staring into the camera, made even the staunchest conservative opposition soften their critiques. Mexican assistance to the Spanish Republic culminated with the arrival of Spanish refugees from 1937 to 1950. While Cárdenas supporters perceived Mexico as profiting from this influx of Spanish blood, and modern, educated citizens, opposition forces feared further radicalization of government policies. Both the Spanish children and the later political refugees became a symbol of the Republican cause with which Cárdenas sympathized. Cárdenas managed to reinforce concepts of internal unity and national pride through charity and philanthropy, while simultaneously dismantling accusations of him being antifamily and on the road to Communism. The concept of using charity strategically can be seen as closely connected to the formation of a modern nation. The Spanish Republicans tied nicely into grandiose ambitions of the government in a period of increased state power. The influx of Spaniards became an opportunity for Mexico to advance its regional ambitions as a cultural and political leader in Latin America.

LAZARO CARDENAS WITH YOUNG SPANISH REFUGEES.

Bibliography

Boletín al servicio de la emigración española (Mexico City), Aug. to Oct. 1939.

Cárdenas, Lázaro. Obras: I apuntes.1913‑1940. Mexico City:

Universidad Nacional

Autónoma de México, 1972.

Cimet, Adina. Ashkenazi Jews in Mexico:

Ideologies in the Structuring of a Communitv.

Albany: State University of New York Press, 1997.

Centro Republicano Español. México y la república española: Antología

de documentos.

1931-1977. Mexico City:

Centro Republicano Español de México, 1978.

Delavigne, August. "Souvenirs de l’Espagne en Guerre." Gavroche

13: 78 (1994), 11‑13.

Dominquez Pratz, Pilar. Mujeres españolas en México. 1939‑1950.

Madrid: Comunidad

de Madrid, Direccion General de la

Mujer, 1994.

Enriquz Perea, Alberto ed. México y España:

Solidaridad y asilo político. 1936‑1942. Mexico City: Secretaría de

Relaciones Exteriores, 1990.

Excelsior (Mexico City), May‑June

1937 and May‑June 1939.

Fagen, Patricia W. Exiles

and Citizens: Spanish Republicans in Mexico.Austin: University

of Texas Press, 1973.

Fein,

Seth. "Hollywood and the United States‑Mexico Relations in the

Golden Age of Mexican Cinema." Ph.D. dis., University of Texas at Austin,

1996.

Foulkes, Vera. Los niños de Morelia y la

escuela "España‑México:" Consideraciones analíticas sobre un

experimento social. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México,

1953.

Gonzalez, Luis. Historia de la revolución

mexicana. 1934‑1940: Los dias del presidente Lázaro Cárdenas. 1981

Reprint, Mexico City: El Colegio de México, 1988.

Gonzalez Navarro, Moises. Los extranjeros en

México y los mexicanos en el extranjero. 1821‑1970. Vol. 3. Mexico

City: El Colegio de México, 1994.

Herf,

Jeffrey. "From Periphery to Center: German Communists and the Jewish

Question, Mexico City, 1942‑1945." In Divided Memory: The Nazi

Past in the Two Germanys. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1997.

Historia Gráfica de la Revolución. 1900‑1946. Mexico City: Archivo Casasola, Cuaderno

24. n.d.

Ley general de población. Mexico City:

Ediciones Botas, 1936.

Lida, Clara E. Inmigración y exilio:

Reflexiones sobre el caso español. Mexico City: Siglo Veintiuno, 1997.

Martinez Legorreta, Omar. Actuación de

México en la Liga de las Naciones: El caso Español. Mexico City:

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1962.

Mexico. Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. Memoria

(1937‑1940). Mexico City: Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores, 1938‑1941.

Navas Ruiz, Ricardo. Jose Vasconcelos y la educación en México. Salamanca:

Colegio

de España, 1984.

New York Times, May‑June 1937 and

May‑June 1939.

Payá Valera, Emeterio. Los niños españoles

de Morelia: El exilio infantil en Mexico. Mexico City: Edamex, 1985.

Partido Nacional Revolucionario. Plan sexenal. Mexico City: n.

p., 1937.

Pla Brugat, Dolores. "Características del

exilio español del 1939." In Una inmigracion privilegiada:

Comerciantes, empresarios y profesionales españoles en México en los siglos

diecinueve y veinte. Edited by Clara E. Lida. Madrid: Alianza Editorial,

1994.

--------.

Los niños de Morelia: Un estudio sobre los primeros refugiados españoles

en México. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e

Historia, 1985.

Reyes Perez, Roberto. La vida de los niños

iberos en la patria de Lázaro Cárdenas. Mexico City: Editorial America,

1940.

Sherman,

John W. "Reassessing Cardenismo: The Mexican Right and the Failure of a

Revolutionary Regime, 1934‑1940.” The Americas 54: 3 (Jan. 1998),

357‑378.

Sinaia: Diario de la primera expedición de

republicanos españoles a México. Sinaia n.p., l940;

Mexico City: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Coordinación de Difusion

Cultural, La Oca and Redacta, 1989.

Solorzano de Cárdenas, Amalia. Era otra cosa la vida. Mexico

City: Editorial Patria,1994.

Sosa Elizaga, Raquel. Los códigos ocultos

del cardenismo. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1996.

Stepan,

Nancy Leys. "The Hour of Eugenics:" Race, Gender, and Nation in

Latin America. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991.

Universal. El (Mexico City), June 1937,

May and June 1939.

U.S.

National Archives. Records of the Department of State Relating to Internal

Affairs of Mexico. 1930-1939. RGM 1370 "immigration" files

812.55/252‑812.5562/25.

Vasconcelos, Jose. La raza cósmica. Misión

de la raza iberoamericana: Argentina y Brasil. Buenos Aires: Espasa‑Calpe,

1948.